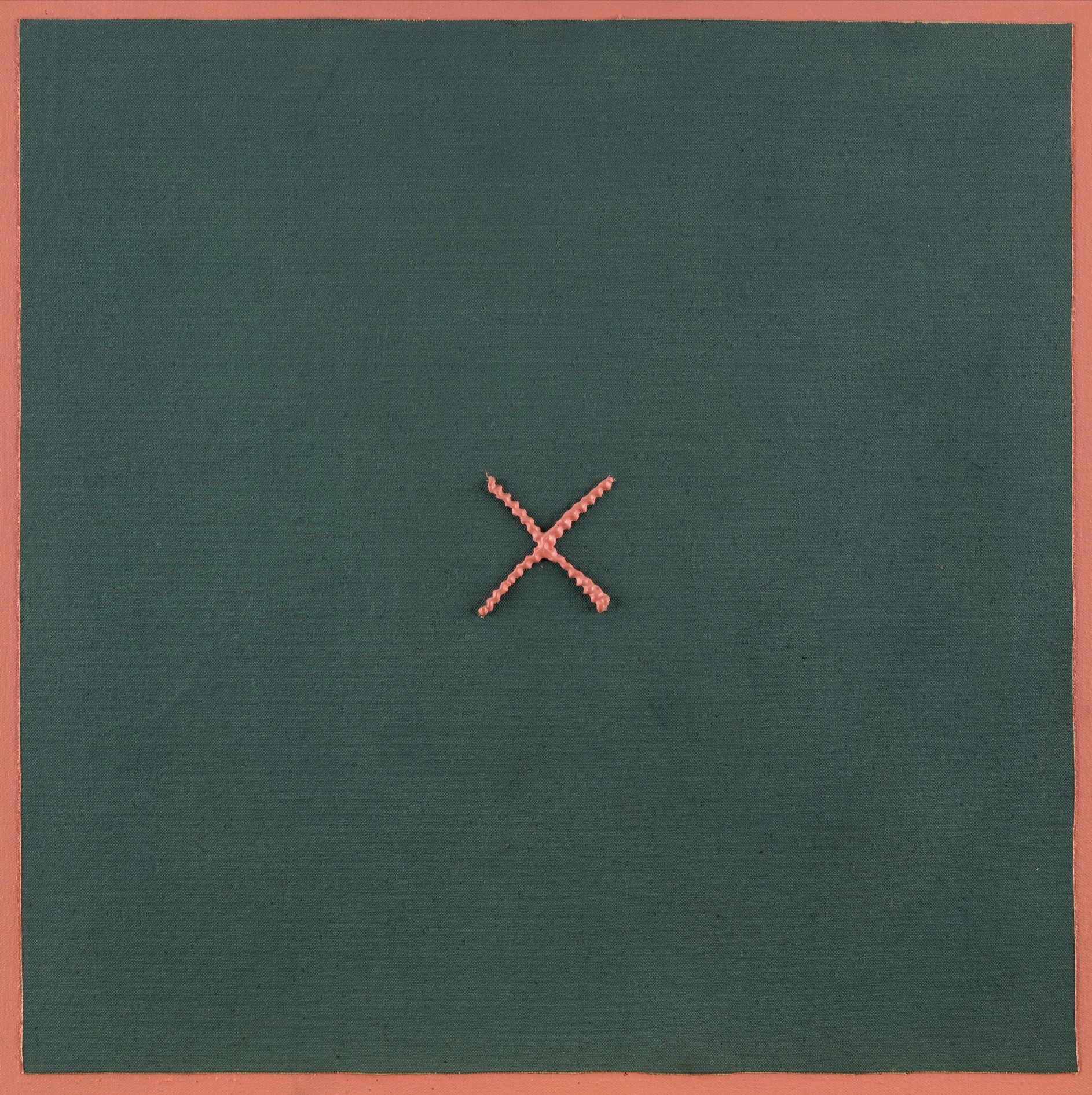

Dolly Sod, 1973, Acrylic on canvas mounted on canvas, 18 x 18 in

Untitled, 1978, Acrylic on canvas, 79" x 58 1/8" x 2 1/2"

Flicker of Recognition, 1984, Oil on canvas, 54 1/2" x 80" x 1 1/2"

Mambo, 1987, Oil on canvas, 88 1/2" x 61 1/2" x 1 1/2"

Slide, 1987, Oil on canvas, 63 5/8" x 48 3/4" x 1 5/8"

Untitled, 1983, Tempera on canvas board, framed

Face, 2005, Oil and charcoal on canvas, 24" x 20"